When asked about the inspirations for her characters, author of The Hundred Wells of Salaga, Ayesha Harruna Attah, shares that her “goal was to write fully rounded people…because even the kindest people are capable of cruelty, and people tagged as evil can do the kindest acts.” This seems to be the heart of her novel; in her goal to bring an authentic voice to her great-great-grandmother — a slave in Salaga — Attah creates a complex, nuanced, and unrelentingly honest depiction of the slave trade in precolonial Ghana. The novel explores the experiences of royalty and the impoverished, of women abused by men and slaves abused by owners and traders. Attah humanizes characters that history paints as villains, not only depicting the complexities of human nature, but inviting readers to engage with the ways in which society normalizes and justifies systemic oppression. Just as Attah herself notes, her characters and readers are “capable of cruelty and…kindness,” emphasizing not only the duality of human nature, but the role choice plays in it as well.

The Hundred Wells of Salaga alternates between the viewpoints of Aminah and Wurche, two women of dramatically differing social classes. While the two women’s stories technically collide in the latter half of the book, their narratives never truly intertwine. No relationship ever develops between the women, and they ultimately part ways. Attah subverts readers’ expectations in this way; while a conventional narrative might join the women together to overcome their shared oppressor — the patriarchal royal society — Attah reminds readers this is impossible, as Wurche is, to Aminah, an active participant of the oppressive society in which she lives.

The novel ultimately ends on a note of hope. Though both Wurche’s and Aminah’s perceptions of happiness evolve through the course of the novel, their stories end with renewed promise of what’s to come. Just as Attah argues that humans are “capable of cruelty…and kindness,” she shows they are capable of choice and change, too. Despite the frank exploration of a painful history, Attah’s narrative is not exposing or shaming; it is humanizing, both in the good and bad, the painful and the healing. A balanced blend of fact and fiction, The Hundred Walls of Salaga offers two energized voices to the historical fiction genre, breathing life into an important story of politics, womanhood, and, ultimately, humanity in precolonial Ghana.

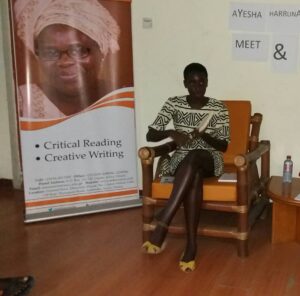

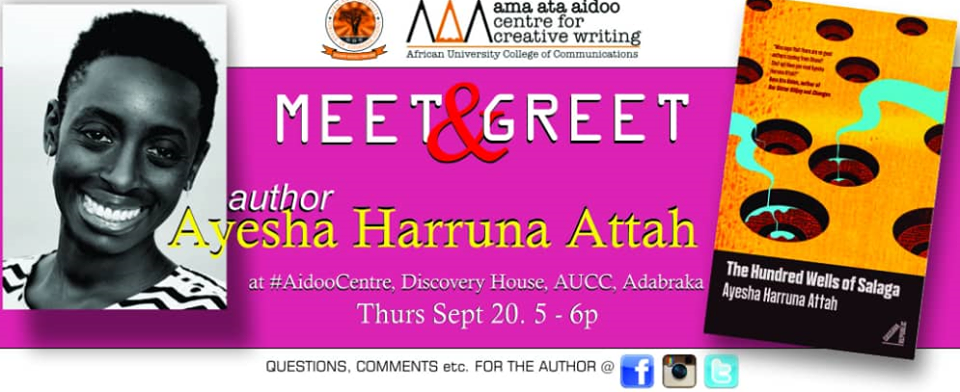

Ayesha Harruna Attah visited students at AUCC to share her views on, among others, her writing process, the important of names in her writing, and her least favorite parts of the writing/publishing chain.