In the late 1970s, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania was one of the most rapidly growing cities in the world. Each year, thousands of young men and women left their rural homes and made their way to the city, expanding the squatter settlements and the ranks of the city’s youth population. The global economic recession of the 1970s, followed a decade later by structural adjustment policies and the gradual collapse of Tanzania’s socialist experiment, led to great hardship for most urban residents. Public buses ground to halt for lack of petrol, and Dar es Salaam residents queued for hours outside government cooperative stores to access basic necessities, such as soap, tea, flour and rice, only to find that the shelves were often empty. More gallingly, despite an official public rhetoric of egalitarianism, the city was a place of visibly dramatic inequalities, where the corrupt could prosper and those who followed the rules often found themselves living in dire poverty. Yet in this context of scarcity, at least one thing could be found in abundance: love stories.

Swahili romance novels proliferated in Dar es Salaam in the late 1970s. Every year, tens of thousands of novellas were produced and sold in the city’s informal economy. They were printed on thin, cheap paper, and had titillating cover artwork depicting voluptuous women, kung-fu fighters, guns, suitcases of cash, and motorcycles. The books circulated from person to person, traded along social networks of readers until they eventually began to fall apart from wear and tear. The back covers of the novellas helped amplify the reputation of the writer by displaying his picture and bio, alongside several blurbs of bombastic praise from other young writers. The authors were young migrant men from rural areas, newly arrived in Dar es Salaam, and they circulated throughout the city on foot, selling their books out of briefcases or displaying them at newspaper stands or religious bookshops. These romance stories offer up a kind of unintended archive of the emotional lives of Dar es Salaam’s young men in the mid-1970s through 1980s, the final decade of Tanzania’s socialist experiment.

Swahili romance novels proliferated in Dar es Salaam in the late 1970s. Every year, tens of thousands of novellas were produced and sold in the city’s informal economy. They were printed on thin, cheap paper, and had titillating cover artwork depicting voluptuous women, kung-fu fighters, guns, suitcases of cash, and motorcycles. The books circulated from person to person, traded along social networks of readers until they eventually began to fall apart from wear and tear. The back covers of the novellas helped amplify the reputation of the writer by displaying his picture and bio, alongside several blurbs of bombastic praise from other young writers. The authors were young migrant men from rural areas, newly arrived in Dar es Salaam, and they circulated throughout the city on foot, selling their books out of briefcases or displaying them at newspaper stands or religious bookshops. These romance stories offer up a kind of unintended archive of the emotional lives of Dar es Salaam’s young men in the mid-1970s through 1980s, the final decade of Tanzania’s socialist experiment.

The romance novellas are formulaic and share similar casts of characters. They feature young, handsome and athletic male protagonists, fashioned after international celebrities including Bruce Lee, Muhammad Ali and Bob Marley. The heroes are well-versed in global black popular culture and radical political thought, and can quote James Brown songs and Julius Nyerere’s writings with equal ease, yet at the same time, they are rooted in the contemporary material realities of Dar es Salaam. Physically, they are lean from hunger and fit from playing soccer and practicing kung fu. They are often broke. Crammed into shabby apartments with their mates, the protagonists of these novellas nonetheless piece together their outfits from second hand clothes, tailored to the latest fashions on the sewing machines of street tailors. Their elegance in the face of scarcity attests to their taste and street-smarts. They are virtuous, cosmopolitan and frugal. And they are always in love.

A beautiful “girl” is always part of the story. Sometimes she is virtuous and pure, and sometimes conniving and greedy. In these male-authored romance novellas of 1970s Dar es Salaam—and despite the many Tanzanian women writers at the time, the authors of this particular popular genre were men—she is never complex, never has an inner life of her own. The story is not about her; rather her depiction furthers a story that is about young men. Attached to the girl are her conservative parents, who antagonize their daughters’ suitors and stand in the way of love. Take, for example, Juma Mkabarah’s Kizimbani (On the Witness Stand), in which the young Rosa is found dead in the bed of her boyfriend, Joseph Gapa. Rosa’s father comes after Joseph with a machete, publically berates him for stealing Rosa away from his household, calls him a hooligan, and accuses him of killing her. But in a dramatic final courtroom scene, a letter from the departed Rosa is presented in which she reveals that she killed herself out of despair when her parents refused to allow her to marry the boy she loved. Joseph Gapa is exonerated and carried out of the courtroom on the shoulders of a cheering crowd, a hero.

A beautiful “girl” is always part of the story. Sometimes she is virtuous and pure, and sometimes conniving and greedy. In these male-authored romance novellas of 1970s Dar es Salaam—and despite the many Tanzanian women writers at the time, the authors of this particular popular genre were men—she is never complex, never has an inner life of her own. The story is not about her; rather her depiction furthers a story that is about young men. Attached to the girl are her conservative parents, who antagonize their daughters’ suitors and stand in the way of love. Take, for example, Juma Mkabarah’s Kizimbani (On the Witness Stand), in which the young Rosa is found dead in the bed of her boyfriend, Joseph Gapa. Rosa’s father comes after Joseph with a machete, publically berates him for stealing Rosa away from his household, calls him a hooligan, and accuses him of killing her. But in a dramatic final courtroom scene, a letter from the departed Rosa is presented in which she reveals that she killed herself out of despair when her parents refused to allow her to marry the boy she loved. Joseph Gapa is exonerated and carried out of the courtroom on the shoulders of a cheering crowd, a hero.

The great obsession of many of these romance writers was the figure of the sugar daddy. In Kassim Kassam’s Shuga Dedi, the titular character is Fabian Mwaluso, owner of a factory and seducer of the young and beautiful Fatuma: a schoolgirl from a poor family. Fabian is overweight and arrogant, and he seduces Fatuma with a meal of chicken and chips, rides to school in his Mercedes Benz and nights out dancing. In Kajubi’s Kitanda Cha Mauti (Bed of Death) it is Fadhil Magoma, a schoolteacher who sleeps with schoolgirls and impregnates at least one student: the protagonist Diana Kiboko. In the end, Diana kills him, herself and their child. In Mkufya’s The Wicked Walk, Magege is a manager in a factory, drives a Mercedes Benz, and ruthlessly exploits his employees. Outside the workplace, he seduces the young Anna away from her hip and politically righteous boyfriend, the protagonist Deo: a tall, thin, handsome man in bellbottoms and platform shoes, and a fan of Bruce Lee films. In contrast with the young male lovers like Deo, the sugar daddies are fat and old. They are wealthy and can wear expensive imported clothes, but they have no style. They drive around Dar es Salaam’s dilapidated roads in expensive imported cars while young men walk on foot or wait in lines for public buses that may never arrive. They leave their wives and children at home and steal young girls from their rightful partners—young men—by plying them with rides in cars, dinners of chicken and chips, and access to the city’s bars and nightclubs, with bottled alcohol and dinner and dancing. The relationships are always ruinous for the “girls,” who end up dying through botched abortions or suicides, or else destitute and shunned by their communities.

The great obsession of many of these romance writers was the figure of the sugar daddy. In Kassim Kassam’s Shuga Dedi, the titular character is Fabian Mwaluso, owner of a factory and seducer of the young and beautiful Fatuma: a schoolgirl from a poor family. Fabian is overweight and arrogant, and he seduces Fatuma with a meal of chicken and chips, rides to school in his Mercedes Benz and nights out dancing. In Kajubi’s Kitanda Cha Mauti (Bed of Death) it is Fadhil Magoma, a schoolteacher who sleeps with schoolgirls and impregnates at least one student: the protagonist Diana Kiboko. In the end, Diana kills him, herself and their child. In Mkufya’s The Wicked Walk, Magege is a manager in a factory, drives a Mercedes Benz, and ruthlessly exploits his employees. Outside the workplace, he seduces the young Anna away from her hip and politically righteous boyfriend, the protagonist Deo: a tall, thin, handsome man in bellbottoms and platform shoes, and a fan of Bruce Lee films. In contrast with the young male lovers like Deo, the sugar daddies are fat and old. They are wealthy and can wear expensive imported clothes, but they have no style. They drive around Dar es Salaam’s dilapidated roads in expensive imported cars while young men walk on foot or wait in lines for public buses that may never arrive. They leave their wives and children at home and steal young girls from their rightful partners—young men—by plying them with rides in cars, dinners of chicken and chips, and access to the city’s bars and nightclubs, with bottled alcohol and dinner and dancing. The relationships are always ruinous for the “girls,” who end up dying through botched abortions or suicides, or else destitute and shunned by their communities.

As an urban archive, these novellas take us into the intense generational tensions that structured experiences of the city. The young male migrants who came to the city in the 1970s had been to secondary school in the more optimistic years of decolonization, and as citizens of a newly independent nation, had expected to become a new generation of literate, salaried men supporting families in the city. Yet the economic decline of the second half of the seventies laid waste to those ambitions, and they encountered a city starkly different than the one they had envisioned, with skyrocketing unemployment rates and rapidly declining real wages. Marriage was increasingly out of reach as the cost of bridewealth—gifts offered from the family of the husband to family of the wife to solidify the bond between them—was increasingly high, making it impossible for many young couples to form socially recognized families. Forms of adulthood that had been available to their parents and grandparents’ generations, attained through land cultivation and marriage, were increasingly out of reach. In these circumstances, young men in the city found themselves stalled, unable to find public recognition as an adult. In these novellas about love, writers gave voice and pathos to their generation, placing blame at the feet of older generations, and creating a counter-narrative to the more dominant public narrative of degenerate urban youth.

The Swahili romance novellas of 1970s Dar es Salaam were whimsical, raucously imaginative, cheeky and sometimes absurdly far-fetched. They were also dead serious. They lured the reader in with fabulous cover images, bombastic prose and suspenseful plots, and grounded the reader in the emotional contours of urban life as experienced by young African men. At a time when the young and unemployed in cities were blamed for Tanzania’s ills, the writers of romance novellas wrote a new moral script of the city, recasting young transient men in the city as virtuous, emotionally authentic and heroic. The Swahili romance novel made room in the collective imagination for a new kind of urban resident.

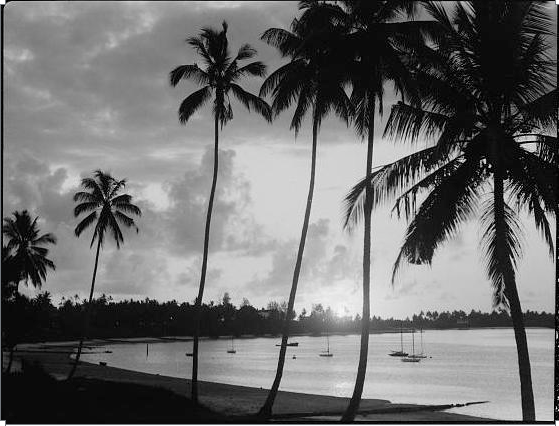

Featured image at top: Tanganyika. Dar-es-Salem. Sunrise seen through palm grove from across the bay, 1936, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

Emily Callaci is an assistant professor of African History at the University of Wisconsin Madison and author of Street Archives and City Life: Popular Intellectuals in Postcolonial Tanzania (Duke, 2017).